COVID-19 can result in prolonged illness, even among young adults without underlying chronic medical conditions.

During April 15–June 25, 2020, telephone interviews were conducted with a random sample of adults aged ≥18 years who had a first positive reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, at an outpatient visit at one of 14 U.S. academic health care systems in 13 states. Interviews were conducted 14–21 days after the test date.

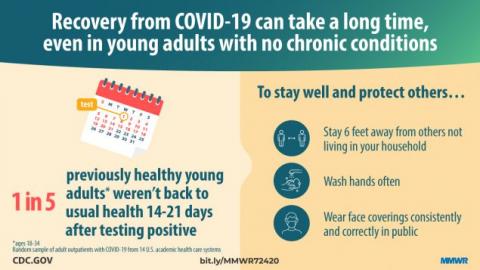

Among 292 respondents, 94% (274) reported experiencing one or more symptoms at the time of testing; 35% of these symptomatic respondents reported not having returned to their usual state of health by the date of the interview (median = 16 days from testing date), including 26% among those aged 18–34 years, 32% among those aged 35–49 years, and 47% among those aged ≥50 years. Among respondents reporting cough, fatigue, or shortness of breath at the time of testing, 43%, 35%, and 29%, respectively, continued to experience these symptoms at the time of the interview. These findings indicate that COVID-19 can result in prolonged illness even among persons with milder outpatient illness, including young adults.

Most studies to date have focused on symptoms duration and clinical outcomes in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19. This report indicates that even among symptomatic adults tested in outpatient settings, it might take weeks for resolution of symptoms and return to usual health. Not returning to usual health within 2–3 weeks of testing was reported by approximately one third of respondents. Even among young adults aged 18–34 years with no chronic medical conditions, nearly one in five reported that they had not returned to their usual state of health 14–21 days after testing. In contrast, over 90% of outpatients with influenza recover within approximately 2 weeks of having a positive test result. Older age and presence of multiple chronic medical conditions have previously been associated with illness severity among adults hospitalized with COVID-19; in this study, both were also associated with prolonged illness in an outpatient population. Whereas previous studies have found race/ethnicity to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19 illness, this study of patients whose illness was diagnosed in an outpatient setting did not find an association between race/ethnicity and return to usual health although the modest number of respondents might have limited our ability to detect associations.

In conclusion, nonhospitalized COVID-19 illness can result in prolonged illness and persistent symptoms, even in young adults and persons with no or few chronic underlying medical conditions. Public health messaging should target populations that might not perceive COVID-19 illness as being severe or prolonged, including young adults and those without chronic underlying medical conditions. Preventative measures, including social distancing, frequent handwashing, and the consistent and correct use of face coverings in public, should be strongly encouraged to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2.